Getting Closer To The Truth About Mobile Phones

By Mark Baard

This new finding, from MIT, should cause scientists to more closely examine the risks to human health posed by mobile phones and other wireless, personal technologies. M.B.

MIT neuroscientists believe they have isolated the brain region just behind the right ear where moral judgements take place.

And they can suspend someone’s ability to judge right from wrong, simply by generating a magnetic field near the same spot where many of us hold our cellular phones and wireless, Bluetooth, headsets.

The researchers findings, announced today :

In both experiments, the researchers found that when the right TPJ (right temporo-parietal junction) was disrupted, subjects were more likely to judge failed attempts to harm as morally permissible.

The technique used by the MIT scientists, transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS), has been described as one that creates virtual lesionson the brain.

Neurostar makes a device that affects mood and behaviour, from outside the head. Photo : Neuronetics

And although TMS’s long term effects on health are not well understood (similar amounts of electromagnetic radiation have been linked to increased cancer risk), the treatment is becoming increasingly popular for everything from tinnitus to depression.

And although TMS’s long term effects on health are not well understood (similar amounts of electromagnetic radiation have been linked to increased cancer risk), the treatment is becoming increasingly popular for everything from tinnitus to depression.

The US military also hopes to use TMS to keep soldiers fighting, without the need to stop for sleep,

via Moral judgements can be altered.

See Original Report

Moral Judgements Can Be Altered

Source : Massachusetts Institute of Technology

MIT neuroscientists influence people’s moral judgements by disrupting specific brain region

CAMBRIDGE, Mass. MIT neuroscientists have shown they can influence people’s moral judgements by disrupting a specific brain region a finding that helps reveal how the brain constructs morality.

To make moral judgments about other people, we often need to infer their intentions and an ability known as theory of mind. For example, if a hunter shoots his friend while on a hunting trip, we need to know what the hunter was thinking: Was he secretly jealous, or did he mistake his friend for a duck?

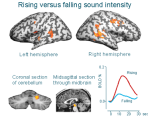

Previous studies have shown that a brain region known as the right temporo-parietal junction (TPJ) is highly active when we think about other people’s intentions, thoughts and beliefs. In the new study, the researchers disrupted activity in the right TPJ by inducing a current in the brain using a magnetic field applied to the scalp. They found that the subjects ability to make moral judgements that require an understanding of other people’s intentions for example, a failed murder attempt was impaired.

The researchers, led by Rebecca Saxe, MIT assistant professor of brain and cognitive sciences, report their findings in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences the week of March 29.

The study offers striking evidence that the right TPJ, located at the brain’s surface above and behind the right ear, is critical for making moral judgements, says Liane Young, lead author of the paper. It’s also startling, since under normal circumstances people are very confident and consistent in these kinds of moral judgements, says Young, a postdoctoral associate in MIT’s Department of Brain and Cognitive Sciences.

You think of morality as being a really high-level behaviour, she says. To be able to apply (a magnetic field) to a specific brain region and change people’s moral judgements is really astonishing.

How they did it: The researchers used a non-invasive technique known as transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) to selectively interfere with brain activity in the right TPJ. A magnetic field applied to a small area of the skull creates weak electric currents that impede nearby brain cells ability to fire normally, but the effect is only temporary.

In one experiment, volunteers were exposed to TMS for 25 minutes before taking a test in which they read a series of scenarios and made moral judgements of characters actions on a scale of 1 (absolutely forbidden) to 7 (absolutely permissible).

In a second experiment, TMS was applied in 500-milisecond bursts at the moment when the subject was asked to make a moral judgement. For example, subjects were asked to judge how permissible it is for someone to let his girlfriend walk across a bridge he knows to be unsafe, even if she ends up making it across safely. In such cases, a judgement based solely on the outcome would hold the perpetrator morally blameless, even though it appears he intended to do harm.

In both experiments, the researchers found that when the right TPJ was disrupted, subjects were more likely to judge failed attempts to harm as morally permissible. Therefore, the researchers believe that TMS interfered with subjects ability to interpret others intentions, forcing them to rely more on outcome information to make their judgements.

Next steps: Young is now doing a study on the role of the right TPJ in judgements of people who are morally lucky or unlucky. For example, a drunk driver who hits and kills a pedestrian is unlucky, compared to an equally drunk driver who makes it home safely, but the unlucky homicidal driver tends to be judged more morally blameworthy.

Source:

Disruption of the right temporo-parietal junction with transcranial magnetic stimulation reduces the role of beliefs in moral judgements, Liane Young, Joan Albert Camprodon, Marc Hauser, Alvaro Pascual-Leone, Rebecca Saxe. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, week of March 29, 2010.

See Original Report

Further Study

MRI Of Mental Time Travel

MRI Of The Human Auditory Cortex

The Lilly Wave and psychotronic warfare